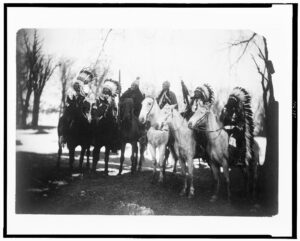

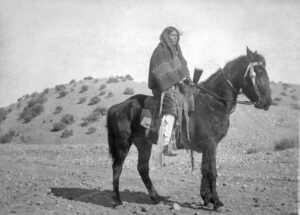

In the annals of American history, the summer of 1874 emerges as a pivotal juncture that reverberates with the complex interactions between Native American tribes and the burgeoning nation. This particular period witnessed a transformative campaign orchestrated by the U.S. Army, a concerted effort to disentangle several indigenous groups from their ancestral territories on the Southern Plains. The tribes in question – the Comanche, Kiowa, Southern Cheyenne, and Arapaho – found themselves at the center of a seismic shift that aimed not only to relocate them to reservations in Indian Territory but also to reshape their existence, ultimately etching a new trajectory onto the tapestry of Texas history.

What unfolded in 1874 represented a marked departure from previous attempts by the U.S. Army to grapple with the challenges of the western frontier. This campaign, known as the Red River War, stands as a historical pivot point, a moment that catalyzed a profound transformation in the dynamics between Native American communities and the encroaching settler society. Its ramifications cast a long shadow over the trajectory of the Southern Plains tribes, heralding a new era in the chronicles of Texas.

The confluence of various factors set the stage for this military intervention aimed at reshaping the lives of the Native American tribes. The 19th century bore witness to a sweeping westward migration of settlers, their dreams of a new life clashing headlong with the nomadic tribes who held a deep-rooted claim to the buffalo plains as their native domain. In response to this burgeoning tension, the U.S. Army erected a network of frontier forts, striving to ensure the safety of these settlers. However, the tumultuous era of the Civil War led to a strategic withdrawal of the military from the western frontier, inadvertently allowing the tribes to seize control over the expansive Southern Plains.

The inevitable call for government intervention resounded, culminating in the formulation of the Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867. This treaty emerged as a formal agreement that sought to earmark two reservations within Indian Territory: one designated for the Comanche and Kiowa and another intended for the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho. In exchange for their compliance, the government committed to providing essential services, housing, sustenance, and even weapons for hunting. However, this initial promise of cooperation was destined for a tragic twist.

The ensuing years bore witness to the gradual collapse of the treaty’s provisions. Commercial buffalo hunters, driven by profit and heedless of the treaty’s obligations, swept into the territories promised to the Southern Plains Indians. The profound consequence of their unbridled slaughter was the near-extermination of the buffalo herds that had long sustained the tribes. This decimation unfolded at an alarming pace between 1874 and 1878, leaving the tribes bereft of their primary source of sustenance and cultural identity. Curiously, while the buffalo were eradicated with impunity, the U.S. government remained inert, an inaction that would come to haunt the indigenous communities.

The promises that the U.S. government had solemnly made devolved into mere hollow echoes. Basic provisions were not only insufficient but often of distressingly poor quality. The stark disjunction between the traditional roaming lifestyle of the tribes and the rigid confines of the reservations generated a simmering discontent. By the cusp of the late spring in 1874, a palpable unease permeated the reservations. As conditions continued to deteriorate, a growing number of indigenous individuals abandoned their confined circumstances to reunite with renegade bands that had retreated to the Texas plains. Within tribal circles, murmurs of defiance and conflict echoed, coupled with fervent aspirations to reclaim their ancestral territories from the encroaching tide of settlers.

In the midst of these turbulent times, a charismatic leader, Isa-tai of the Quahadi Band of Comanches, emerged as a transformative figure. Endowed with a powerful aura, Isa-tai emerged as a prophetic voice, a harbinger of conflict and change. Fueled by desperation, the tribes found themselves at a crossroads: confronted with the specter of starvation or the call to arms. In the face of such stark choices, Isa-tai’s potent rhetoric gained traction, compelling the Indian leadership to consider the prospect of striking back against the expanding settlers. Thus, a plan took shape, one that centered on a bold assault on the newly established settlement known as Adobe Walls.

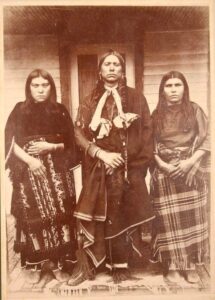

In the early hours of June 27, 1874, under the leadership of Isa-tai and the esteemed Comanche chief Quanah Parker, around 300 Native American individuals converged upon Adobe Walls. The intent was to execute a surprise attack, overwhelming the settlers and seizing the settlement. However, the settlers, numbering a mere 28, were armed with long-range rifles and displayed remarkable resilience, thwarting the assault. This pivotal engagement marked an inflection point, galvanizing the tribes into action.

The aftermath of this clash served as a turning point that reverberated far beyond the confines of Adobe Walls. The confrontation at Adobe Walls acted as a catalyst, spurring the U.S. Army into action and setting the stage for a comprehensive campaign to subdue the Southern Plains tribes. This marked a pronounced shift in the Army’s strategy, one that prioritized the safeguarding of friendly Indians on reservations while unflinchingly pursuing and dismantling hostile factions, transcending geographical and jurisdictional boundaries. The overarching objective was starkly defined: to dislodge the Indian groups from their Texas strongholds and clear the path for Anglo-American colonization.

This military endeavor hinged on a multi-pronged approach, involving five distinct columns that converged upon the Texas Panhandle. Each of these columns, led by figures of prominence such as Colonel Nelson A. Miles and Lieutenant Colonel John W. Davidson, executed a synchronized yet relentless offensive. The strategy aimed at enveloping the region, thereby denying the tribes any avenue of escape. This comprehensive approach sought to maintain an unrelenting pressure until the tribes suffered a decisive, debilitating defeat.

Over the course of the Red River War of 1874, as many as 20 engagements occurred between the U.S. Army and the Southern Plains Indians, each representing a moment of intense confrontation. The superior resources and relentless determination of the Army drove the tribes into retreat, resulting in a protracted series of clashes that inexorably narrowed the room for maneuver. Eventually, the tribes found themselves at a crossroads, a juncture where the only alternatives were surrender or annihilation.

The culmination of these efforts unfolded in June 1875, as Quanah Parker, accompanied by his Quahadi Comanche band, entered Fort Sill to formally surrender. The Red River War came to a close, marked by the tribes’ acknowledgment of defeat and the recognition of their inexorable displacement from the buffalo plains. This surrender not only signified the end of a formidable resistance but also the extinguishing of a way of life that had endured for generations.

Reflecting upon this tumultuous period, it becomes evident that the Red River War of 1874 left an indelible mark on the pages of history. The campaign’s ramifications were profound and far-reaching, recalibrating the dynamics between indigenous communities and the forces of colonization. The campaign encapsulated the ethos of an era marked by change, conflict, and transformation, and it continues to serve as a lens through which to understand the intricate interplay of culture, power, and conquest that defined the American frontier. General Philip Sheridan’s assessment that this campaign represented a pinnacle of success resonates with the passage of time, underscoring the campaign’s impact as one of the most comprehensive and consequential chapters in the annals of Indian-White relations on the American frontier.