The Comanche people were bound by language and tradition to their kin, the Eastern Shoshone of Wyoming. In the vibrant tapestry of the 16th century, the Comanche broke away from the Shoshone, embarking on a momentous journey southward, setting their sights on the untamed lands of Colorado. There, like the Eastern Shoshone, they transformed into relentless nomads of the Great Plains, skilled in the art of bison-hunting.

Legend whispers that the Great Plains beckoned them forth, lured by the embrace of wetter climates that cradled a burgeoning bison population. It was a land ripe with promise and opportunity, and the Comanche heeded its call.

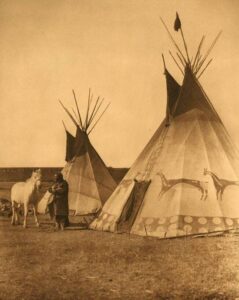

In the southern reaches of Colorado, the Comanche forged an unbreakable alliance with the Ute tribe, two kindred spirits bound by shared ways of survival. As the late 17th century bathed the landscape in the hues of time, both tribes embraced a similar rhythm of life. As autumn’s chill set in, the Comanche splintered into small, agile groups, their spirits attuned to the ways of the hunter-gatherers in the picturesque western realm of Colorado, caressed by the San Luis Valley’s beauty.

Yet, with the birth of each new spring, the pulse of the Comanche and Ute quickened. Like thundering herds, they crossed the formidable Sangre de Cristo Mountains, leaving a trail of stories etched in the earth. Together, they journeyed eastward, drawn to the boundless expanse of the Great Plains, where bison roamed in abundance, a testament to nature’s blessings.

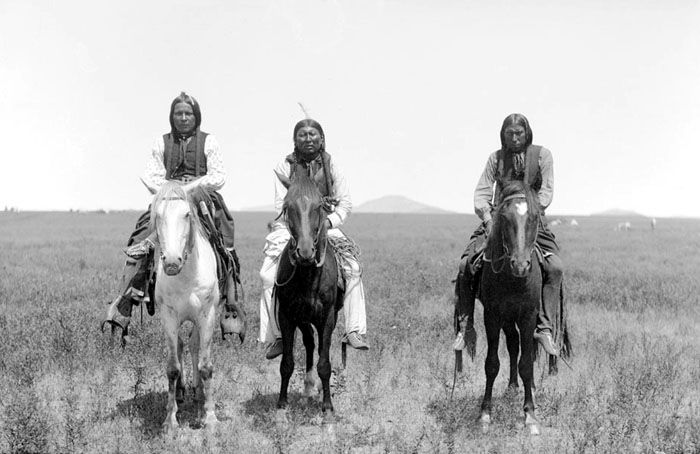

In the midst of these times, fate’s hand bestowed a gift upon the Comanche: the elusive secret of taming horses. The yearning for freedom, intensified by the tales of Spanish horses available to native peoples after the Pueblo peoples rose up and cast out the Spanish invaders from New Mexico, was finally fulfilled in the 1680s. The swift and nimble horses granted the Comanche the wings of wind, turning them into wide-ranging nomads, masters of the open plains.

The tapestry of history weaves on, and the first European mention of the Comanche resounds in 1706. Spanish soldier Juan de Ulibarri brought forth tales from the distant Pueblo settlement of Taos, where rumors danced in the air. Whispers of impending attacks by the “infidel enemies,” the Ute and Comanche tribes, reached his ears. Yet, fate took another turn, and the feared assault never came to pass. Nevertheless, a legacy of fearsome raiders, fierce and unyielding, took root in the annals of time, forever etching the Comanche into the realms of legend.

The Ute word “kɨmantsi,” a potent whisper of animosity, bestowed the name by which the Comanche would be known. Yet, they called themselves “nɨmɨnɨɨ,” resonating with a gentle meaning, “people,” an identity close to their hearts. When the French encountered them before the sun of 1740 kissed the horizon, they bestowed upon them the name “Padouca,” a title they also granted the Apache, igniting confusion in the early chapters of French interactions with these awe-inspiring peoples, whose history flowed like a river through the ages.

Comanche history in the eighteenth century unfolds into three distinct and captivating chapters, each interwoven with tales of alliances, conquests, and challenges with neighboring peoples.

The first chapter revolves around the Comanche’s entanglements with the Spanish, Puebloans, Ute, and Apache tribes of New Mexico. By the late 18th century, two distinct groups of Comanche had emerged. The western bands, dwelling in the vast expanses of New Mexico, Colorado, Kansas, and the Texas panhandle, had their gaze fixed upon the Spanish settlements in New Mexico. On the other hand, the eastern bands, dwelling in the enchanting landscapes of southwestern Oklahoma and central Texas, had their eyes set on the Spanish settlements in Texas. As they navigated their complex relationships with these neighboring peoples, a new challenge loomed on the eastern border of the Great Plains—the French and their formidable Indian allies. And this was just the beginning, for the 19th century would bring even more challenges, with the arrival of the emigrant Five Civilized Tribes of Oklahoma and the Anglo settlers of Texas, forever altering the course of Comanche history.

One remarkable aspect of the Comanche people was their legendary horsemanship. They rode with grace and skill, a sight to behold, as they pursued bison—their lifeblood, their main source of sustenance. In the early 18th century, the Ute and Comanche, perhaps junior partners in their alliance at the time, rose to prominence on the northern frontier of Spanish New Mexico. While their activities often involved the pilfering of livestock, tensions escalated when the governor of New Mexico launched a fateful attack on a peaceful Ute/Comanche camp. Lives were lost, captives were taken, and the conflict grew more heated. The Ute and Comanche struck back, launching a massive raid in the Taos region that claimed lives. The Spanish responded with an expedition comprising more than 700 troops, mainly consisting of Pueblos and Apache, but the elusive Ute and Comanche proved difficult to find. Instead, the expedition discovered the plight of the Apache peoples in southern Colorado, who suffered at the hands of the Ute and Comanche. Some Apache bands sought refuge closer to the Spanish settlements in New Mexico, while others clung to their hostility towards both the Spanish and the Comanche.

In the following decades, the Comanche solidified their hold on the Arkansas River valley of Colorado, reaching a pivotal point in the 1730s when they became the pioneering fully-mounted, bison-hunting nomads of the Great Plains—the very first American Indians to adopt an equestrian lifestyle. Their mastery of horsemanship allowed them to push the Apache south and westward, expanding their territory and cultural dominance. As the Comanche grew in strength, their ties with the Ute began to fray, with cultural and political divisions emerging in the 1730s. In 1749, the Ute sought aid from the Spanish in New Mexico to confront the Comanche in a war that would persist throughout the 18th century. While the Ute’s concerns remained important, the Comanche faced even grander challenges on their remarkable journey through history.

In 1749, the captivating lands of New Mexico and its Puebloan and Spanish inhabitants were home to a population of merely 15,000 souls. Amidst this delicate balance, the mighty Comanche, undeterred by military setbacks, began their ascent to dominance over the colony. A dance of trade and raid unfolded, as the Comanche asserted their prowess.

The echoes of conflict resounded through the canyons in 1747, as a force of more than 500 Spanish and Puebloan men unleashed their fury upon a Comanche and Ute camp, leaving a trail of devastation. Lives were lost, captives taken, and the winds of change whispered. In 1751, history repeated itself, as Spanish and Puebloan troops skillfully trapped 300 Comanche in a box canyon, a moment that would forever be etched in the annals of time. Carnage unfolded, lives were extinguished, and the Comanche, facing these defeats, sought peace. The peace agreement of 1752 favored them, granting trade privileges and recognition as a sovereign nation, empowering them to wage war against the Ute.

However, peace, like shifting sands, proved fragile. The year 1767 ushered in a relentless campaign led by the Comanche, leaving hundreds of Spanish and Puebloans in its wake, and the Rio Grande valley of New Mexico lay in ruins. The Spanish responded, unleashing a powerful response in 1774. Their soldiers surrounded a Comanche band, and a heart-wrenching spectacle unfolded as lives were lost, families torn apart, and the fates of the captured sealed in sorrow. Yet, the Comanche persevered, strengthening their grip on New Mexico, undeterred by the trials they faced.

A significant turning point arrived in 1779, when the valiant Governor Juan Bautista de Anza, renowned for his expertise in Indian warfare, took the battle directly to the Comanche in their heartland. With a formidable force at his side, including Ute and Apache auxiliaries, he marched northward, marking a chapter of epic proportions. The powerful Comanche war leader, Cuerno Verde, met his fate in the Greenhorn Valley, Colorado, surrounded by the echoes of battle. While raids did not entirely cease, the idea of peace gained traction, especially when the eastern Comanche in Texas struck a peace treaty, heralding hope for an era of reconciliation.

Among the western Comanche, the struggle for peace was personified by the enigmatic White Bull. The peace faction within the Comanche, determined to see an end to the bloodshed, took decisive action and granted the power to make peace to the esteemed leader, Ecueracapa. Moments of tension and negotiation followed, with Pecos and Comanche camps bearing witness to history’s unfolding. Finally, in July 1786, a signed treaty was sent to Mexico City, sealing the peace of 1786, a momentous event that brought an end to major hostilities between the Comanche and the Spanish and Puebloans of New Mexico.

This newfound peace ushered in an era of cooperation. The Comanche and Spanish joined forces against their mutual enemy, the Apache. Settlements extended eastward onto the Great Plains, and the population of New Mexico soared. Tokens of goodwill flowed, as the Spanish lavished the Comanche with gifts, lifting trade restrictions on weapons and ammunition. Even a few Comanche children attended Spanish schools, symbolizing a unique and complex intermingling of cultures. Travelers ventured across the Plains, unburdened by fear, as a class of traders, the Comancheros, paved the way for trade between Spanish goods and the Comanche heartland in the Texas panhandle, where buffalo robes, meat, and horses exchanged hands.

With New Mexico as a haven, the Comanche embarked on raids that pierced the heart of Mexico, evoking awe and trepidation. In 1841, when faced with the Mexican central government’s orders to wage war on the Comanche, New Mexico Governor Manuel Armijo hesitated, for such a conflict would spell doom for the land he held dear.

Thus, the tale of Comanche history intertwined with the vibrant landscapes of New Mexico and Texas, leaving an indelible mark on the tapestry of time. From triumphs to tragedies, from fierce battles to cherished peace, their legacy echoed through the ages.

In the 18th century, the struggling Spanish colonies in Texas were locked in a fierce battle for survival, facing relentless hostility from the Apache and Comanche tribes. With a mere population of 3,000, the Spanish colonies fought tooth and nail to endure in this harsh land. Yet, amid the hardships, alliances with various Indian tribes provided glimmers of hope.

In the annals of history, the Comanche’s first appearance in Spanish Texas was in 1743, a scouting party marking their presence in San Antonio. By that time, the formidable Comanche had already driven the Apache off the Great Plains, forcing them into southern Texas where they became the Lipan Apache. Some sought refuge in the desolate deserts of the southwest, while others formed uneasy alliances with the Spanish in New Mexico. The Spanish and Lipan, though once at odds, found common ground in 1749 as they united to resist the Comanche threat, forging a fragile peace that would prove short-lived.

The 1750s saw the rise of a powerful alliance, as the Comanche joined forces with the Norteños, a group of tribes residing north of the Spanish settlements. Among these allies were the Wichita, with their influential sub-tribe, the Taovayas, having migrated southward to the Red River valley of Oklahoma and Texas. Alongside the Tonkawa of the Texas plains and the Hasinais, the westernmost of the Caddo people, they formed a formidable alliance. In 1758, this united force, including the Comanche, pillaged the San Saba Mission, a strategic Spanish endeavor aimed at converting the Lipan to Christianity. Seeking revenge, a Spanish and Indian army launched an assault on two fortified Taovaya villages in the Red River Valley, only to be thwarted in the Battle of the Twin Villages.

Initially, the Comanche engaged in trade with the agricultural Wichita, exchanging buffalo pelts and meat for maize. The Wichita also served as intermediaries, facilitating the trade of Comanche horses to Spanish colonies in Louisiana. However, as the 1770s unfolded, the alliance faltered. Devastating outbreaks of European diseases weakened the Wichitas, prompting the Comanche to shift their focus eastward, directly trading with the Spanish and French populations of Louisiana. Simultaneously, the Spanish faced threats from the formidable Osage tribe on their northeastern frontier and Apache raids south of the Rio Grande River in Mexico. Seeking peace, they extended an olive branch to the Comanche. Yet, tragedy struck in 1778 when a Comanche peace delegation was massacred in eastern Texas, sparking a vicious assault by the Comanche on Spanish settlements and other Indian tribes. The Spanish dream of establishing a powerful colony in Texas to counter the advance of British and French colonists seemed to crumble as the Comanche launched relentless attacks, leaving the Spanish reeling.

However, in 1780-1781, a smallpox epidemic swept through the Indian population, impacting even the Comanche. As both Spanish and Comanche realized they had other interests and common enemies, a shift towards peace began to emerge. Guided by the mediation of the Wichita, negotiations between Pedro Vial and the Eastern Comanche, spearheaded by Comanche-speaking Francisco Xavier Chaves, brought about an agreement in 1785. This accord involved generous gifts to the Comanche and the return of all Spanish prisoners held captive by the tribe. Such a significant development paved the way for a similar peace agreement between the Spanish of New Mexico and the western Comanche in 1786, marking a turning point in the turbulent history of Spanish Texas and the Comanche.

In the grand tapestry of history, the French had few direct encounters with the mighty Comanche. Instead, their interactions were indirect, as they traded with various Indian tribes residing on the eastern border of the Great Plains. Early in the 18th century, French traders thrived along the lower Missouri River and in the vast expanse of Louisiana. Unlike the Spanish, whose interests encompassed colonization, exploitation of mineral wealth, and the spread of Christianity among Native American peoples, the French were primarily driven by economic pursuits.

In 1720, the Spanish sought to expel French traders from the plains and dispatched a military expedition, only to meet a tragic end at the hands of the Pawnee in Nebraska. However, the French did make some headway in their quest for contact with the Comanche, as evidenced by the encounter between the Mallet brothers and the “Laitane” (Comanche) in 1739 along the Arkansas River in Colorado. This interaction paved the way for a significant peace agreement between the Wichita and the Comanche in 1746, mediated by the French.

Amidst the sprawling plains of the eastern Great Plains, the Comanche encountered formidable adversaries, chief among them the Osage tribe. The Osage’s staunch resistance barred the Comanche from venturing eastwards beyond certain territories in Kansas and Oklahoma. The 18th century saw the Osage expand from their Missouri homeland onto the Great Plains to hunt bison, fulfilling the French demand for bison robes and slaves. The Osage enjoyed ready access to French products, including valuable firearms. As a result of the Osage’s hostility, the Wichita, trusted trading partners and allies of the Comanche, were forced to migrate southward to the Red River Valley of Oklahoma and Texas, leaving their former lands in northern Oklahoma and southern Kansas around 1750.

Meanwhile, in northern Kansas and Nebraska, the Comanche and Pawnee clashed in sporadic warfare, their paths fraught with raids for slaves and horses. Battles and skirmishes marked their interactions as both tribes sought to assert their dominance in the region. These encounters with the Pawnee, another powerful tribe allied with the French, added yet another layer of complexity to the Comanche’s interactions with the European powers.

By the dawn of the 19th century, the Comanche had evolved into a formidable force, controlling a vast expanse of 200,000 square miles in the Great Plains. Their large herds of horses served as a valuable commodity, and the seemingly endless bison herds sustained their way of life. However, the smallpox epidemic of 1780-1781 dealt a significant blow to their numbers, and although recurring smallpox and other European diseases continued to take their toll, the Comanche’s population persisted around 20,000, bolstered by captives adopted into their tribe.

In 1790, the Comanche found new Native American partners, with 2,000 Kiowa and Kiowa-Apache joining them in Comancheria as allies. Amid the delicate balance of “accommodation and antagonism” with the Spanish, peace agreements endured, even though the French were no longer a presence after selling Louisiana to the United States in 1803.

The arrival of Anglo-Americans on the borders of Comancheria brought both promise and peril for the Comanche. As the Spanish presence dwindled, the Americans surged, with their vast numbers creating new opportunities and challenges. The United States boasted a population of 10 million by 1820, with Anglo-Americans settling in Texas and creating a robust market for Comanche horses and mules. Irish-born Phillip Nolan was among the first American traders to venture into Comanche territory in the 1790s.

The Anglo market provided the Comanche with a lucrative trade, enabling them to acquire goods and products previously available only through their interactions with the Spanish and French. Yet, this newfound market also heightened tensions and conflicts. As the Anglo-American presence grew, so did their influence, altering the dynamics of the Comanche’s interactions with the European powers.

However, amidst the changing times, the Comanche maintained their identity as a powerful and influential nation. They adapted to the shifting political landscape, forming strategic alliances and engaging in trade with the various European powers and other tribes. Nevertheless, the Comanche’s aspirations for independence and control over their territories remained unwavering.

The peace with the Spanish in Texas began to falter after 1795, and the Mexican War of Independence, which commenced in 1810, further strained relations. The Comanche’s tribute, once provided by the Spanish, diminished as Mexico faced resource constraints in its remote provinces. In 1822, Mexico sought to quell the Comanche threat by inviting Comanche leaders to Mexico City, culminating in a treaty granting trading privileges to the tribe.

As the Mexican government opened Texas to foreign settlers in 1824, the Anglo-Americans, who were already trading extensively with the Comanche, swarmed into the region. The concern of the Mexicans was real, and tensions escalated. In 1825, 330 Comanche rode into San Antonio, pillaging and reveling for six days. In 1832, 500 Comanche occupied San Antonio with little resistance from Mexican soldiers. The weakened state of Mexican Texas set the stage for the Anglo-Americans to claim the independence of Texas from Mexico in 1836.

The once-mighty Comanche, with their storied history and territorial dominance, faced an uncertain future as they navigated the winds of change in this rapidly transforming world. As the Anglo-Americans solidified their hold over Texas and expanded westward, the Comanche found themselves confronting new challenges and threats to their way of life.

The influx of Anglo settlers and their insatiable demand for land and resources put immense pressure on the Comanche’s traditional territories. The vast herds of bison, once a symbol of their abundance and sustenance, dwindled due to overhunting by both the newcomers and Native American tribes forced to compete for resources. The Comanche had long relied on the bison for their livelihood, so the depletion of these majestic creatures deeply impacted their ability to maintain their nomadic lifestyle.

The Comanche’s interactions with the Anglo-Americans were marked by both collaboration and conflict. The Anglo settlers sought to control the vast prairies, while the Comanche fiercely defended their ancestral lands and way of life. Raids and skirmishes became more frequent as tensions between the two groups escalated. The Comanche were formidable warriors, skilled horsemen, and masters of guerrilla warfare, posing a formidable challenge to the encroaching Anglo-American settlers.

The Texas Rangers, a group of frontier lawmen, emerged as a prominent force in confronting the Comanche threat. The Rangers engaged in a series of campaigns to push back against Comanche raids and secure the borders of the rapidly expanding Republic of Texas. However, the Comanche’s resiliency and adaptability defied easy containment, and they continued to pose a formidable challenge to the settlers.

Throughout the first half of the 19th century, the Comanche’s influence on the plains began to wane, largely due to the depletion of bison and the increasing encroachment of Anglo-American settlers. As their traditional way of life faced mounting pressures, some Comanche bands began to consider the advantages of adopting a more settled lifestyle, cultivating crops and engaging in trade.

While some Comanche groups attempted to adapt to the changing circumstances, others continued to fiercely resist the Anglo-American presence, holding onto their ancestral lands with determination and pride. The Comanche’s fierce spirit and dedication to their cultural heritage earned them both admiration and fear among those who encountered them on the frontier.

As the 19th century progressed, the Comanche faced new challenges with the arrival of the railroads, which further encroached upon their lands and disrupted their traditional hunting grounds. The spread of disease, including smallpox and cholera, continued to take a toll on their population, further weakening their once-thriving society.

The Texas-Indian Wars of the mid-19th century intensified the conflict between the Comanche and the Anglo-American settlers. The Comanche faced military campaigns led by the United States Army, resulting in significant losses on both sides. Despite their remarkable resistance, the Comanche could not halt the relentless westward expansion of the United States.

By the latter half of the 19th century, the Comanche faced the grim reality of defeat. Forced onto reservations, their traditional way of life became increasingly untenable. The once-proud Comanche nation found themselves confined to a fraction of their former territory, facing dire living conditions and struggling to maintain their cultural identity.

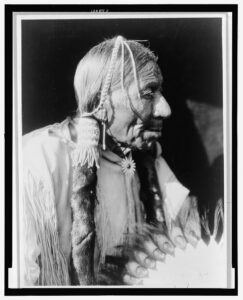

However, even amidst adversity, the Comanche spirit endured. They sought to preserve their language, traditions, and customs, passing them down through the generations. Despite the challenges posed by assimilation efforts, some Comanche leaders worked tirelessly to maintain their cultural heritage and revitalize their communities.

In the 20th century, the Comanche people faced the ongoing challenges of reservation life, along with the broader struggles experienced by Native American communities across the United States. Efforts to revive their cultural practices and revitalize their communities gained momentum, as the Comanche sought to honor their ancestors and protect their heritage for future generations.

Today, the Comanche continue to persevere, proud of their unique history and determined to preserve their cultural legacy. They have become influential voices in advocating for Native American rights and working towards greater recognition and respect for indigenous communities.

The legacy of the Comanche endures as a testament to the strength and resilience of Native American peoples in the face of immense challenges. Their history remains an integral part of the tapestry of the American West, reminding us of the diverse and complex interactions that shaped the nation’s history.

By 1836, a momentous year for Texas as it gained independence, the demographic landscape had undergone a dramatic transformation. The relentless influx of Anglo immigrants had tipped the scales, erasing the once-dominant position of the Comanche and their allies. From a modest population of fewer than 5,000 Spanish inhabitants in the early 19th century, Texas swelled to accommodate 38,000 Spanish and Anglo settlers by 1836. The Native American population, including the formidable Comanche, was estimated to be around 14,000, though this figure may have been an underestimation. The winds of change brought forth not only human migrations but also the scourge of smallpox, which ravaged the Native American communities, further diminishing their numbers in the late 1830s.

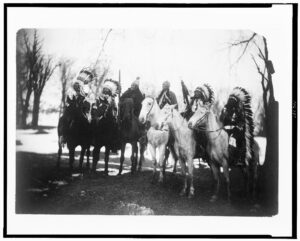

Amidst this shifting landscape, the Comanche sought to secure their place and forge crucial alliances. In 1840, a significant agreement with the southern branches of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes heralded newfound unity and strength for the Comanche. The treaty ended the long-standing conflict on the Comanche’s northern frontier, with about 2,000 Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors pledging allegiance to the Comanche cause. As emissaries of peace, they were welcomed into Comancheria, the vast domain of the Comanche, where the age-old custom of gift-giving cemented the bond between the tribes. The Comanche’s generosity knew no bounds, as they bestowed about five horses from their impressive herds upon each Cheyenne and Arapaho man and woman, a gesture symbolizing trust and cooperation.

The birth of the Republic of Texas brought both opportunity and challenges in dealing with the Comanche. Early on, in May 1836, a violent encounter near Fort Parker, south of Dallas, saw Comanche and Kiowa warriors claim five lives and abduct five women and children, including 9-year-old Cynthia Ann Parker. Little did anyone know that Cynthia Ann’s life would take an extraordinary turn, eventually marrying a Comanche chief named Peta Nocona and giving birth to a son who would grow up to be the legendary Comanche war chief, Quanah Parker, a prominent figure in the tribe’s later history.

The Comanche society, with its egalitarian values and emphasis on acquiring wealth, readily integrated captives into their fold. The need for labor to manage their vast domain made captives valuable assets, and the Comanche were known for their resourcefulness in assimilating diverse individuals into their way of life.

As the political landscape shifted, so did the approach of Texas leaders towards the Comanche. While the first President of Texas, Sam Houston, sought peaceful coexistence, his successor, Mirabeau B. Lamar, took a more direct approach in confronting the Comanche. In 1840, a peace delegation from the Comanche arrived in San Antonio, but a dispute over captives quickly turned into a tragic incident known as the Council House Fight. Texas soldiers killed 35 Comanche, including several chiefs, escalating hostilities.

In response, the Comanche, under the leadership of Buffalo Hump, unleashed the Great Raid of 1840, a formidable campaign that struck fear into the hearts of Texans. Sacking the towns of Victoria and Linville, they left a trail of destruction, taking numerous captives and seizing valuable goods. A retaliatory ambush by Texas militia, with the aid of Tonkawa scouts, in the Battle of Plum Creek, momentarily quelled the Comanche’s bold advances.

The Texas militia later launched an attack on a Comanche village, resulting in the tragic loss of 140 men, women, and children. These clashes left a profound impact on both sides, as the cost of warfare began to take its toll on the finances of the Texas government. As peace became the coveted goal for both Texas and the Comanche, negotiations led to the signing of a treaty in December 1845. The agreement established a line of trading houses, serving as a de facto border between Texas and Comancheria. In exchange for refraining from raids within Texas, the Comanche were granted gifts and trading privileges with the Texan settlers.

These tumultuous times in the mid-19th century reflected the complex and evolving relationship between the Comanche and the rapidly transforming landscape of Texas. The once-dominant Comanche nation navigated shifting political alliances, cultural changes, and the looming specter of westward expansion, all while endeavoring to preserve their unique way of life amidst a rapidly changing world. Their journey, marked by resilience, conflict, and adaptation, would continue to shape the rich tapestry of history in the American West.

When the United States officially annexed Texas in 1845, the fate of the Comanche and other Texas tribes hung in the balance, as new treaties were negotiated to replace previous agreements. In May 1846, on the banks of the upper Brazos River, the Butler-Lewis Treaty was signed, binding the Penateka/Hois Comanches, along with the Ioni, Anadarko, Caddo, Lipan Apache, Wichita, and Waco tribes. The treaty promised peace, friendship, and the establishment of trading posts, as well as the exciting prospect of a Comanche delegation’s visit to the nation’s capital, Washington, D.C. Additionally, a one-time payment of $18,000 in goods was pledged as a gesture of goodwill. While the treaty alluded to a boundary line between Comancheria and Texas, the specifics were left undefined, sowing seeds of ambiguity.

Eager to solidify the treaty, the Comanche delegation embarked on a journey eastward, meeting with none other than President James K. Polk himself. However, with the Mexican War unfolding and Congress preoccupied with more pressing matters, the Senate adjourned without ratifying the treaty, leaving the Comanche feeling betrayed. A crisis was narrowly averted when traders and Indian agents extended credit to provide part of the promised gifts. Though the treaty was eventually amended and ratified in March 1847, tension remained as the Comanche grappled with feelings of uncertainty and unease.

The complexities of governing the Texas tribes soon emerged as a vexing problem. The question of responsibility for dealing with these tribes, whether the federal or state government, remained unanswered until after the Civil War. This policy uncertainty caused confusion and resulted in limited peace under the 1846 treaty.

Seeking stability on their own terms, the German settlers near Fredericksburg and New Braunfels made a pact with the Texas Comanches in May 1847. In exchange for land, the Germans promised a trading post and gifts. However, tensions arose when the Germans encroached beyond the agreed boundary and were slow to fulfill their promises, leading the Comanches to launch raids in response. While a boundary line was eventually established by the Texas governor, its enforcement was a contentious issue. The American army, now in control of the Texas forts on the frontier, felt that it lacked the authority to enforce state laws. Meanwhile, Texas ranger companies operated independently as military units, further adding to the confusion and complexities of governance.

Across Comancheria’s borders, events were set into motion by the Mexican War, which began in 1846. The American army under General Stephen W. Kearny seized Santa Fé and California, creating new dynamics along the Santa Fé Trail, a vital military supply route. Missouri volunteers were sent to garrison forts along this route, leading to confrontations with Plains Indians. While some clashes involved the Pawnee, the Comanche’s exact involvement in other fights with Kiowa, Cheyenne, and Arapaho remained uncertain.

The early part of 1848 brought relative calm, and Texas Comanches even assisted in surveying the route of the new Butterfield (California) trail. However, the California Gold Rush changed everything. The demand for horses by thousands of gold-seekers rushing westward drove the Comanches to meet this new demand, leading to increased horse raids in Texas and even deeper into northern Mexico. In response, the United States called the “Peace on the Plains” conference at Fort Laramie in 1851, aiming to limit intertribal warfare and establish boundaries between tribal territories.

Though almost every Plains tribe attended and signed the Fort Laramie Treaty, the Comanches and Kiowa, dealing with a smallpox epidemic in their villages, were absent. As the southern Plains tribes gathered around Fort Atkinson to receive annuities from the Fort Laramie treaty, large groups of Kiowa and Comanches also arrived, their mood less than amicable. In a bid to avert violence, the American agent distributed $9,000 in gifts to the Comanches and Kiowa, ultimately leading to the signing of their own treaty at Fort Atkinson in 1853. The agreement promised safe passage and an end to raiding in Mexico, with the United States agreeing to pay them $18,000 per year for ten years.

During this period, the Comanches and Kiowas were grappling with multiple challenges, including devastating epidemics of smallpox and cholera. Their population, already impacted by past epidemics, experienced further decimation. The Comanche numbers dwindled drastically, their losses exacerbated by the wave of immigration from the California Gold Rush, which introduced these deadly diseases to the Great Plains. This time of hardship and uncertainty would continue to shape the fate of the Comanche, as they navigated a rapidly changing landscape and the encroachment of settlers in the American West.

The tension between the Comanches and the encroaching white settlers in Texas intensified after the establishment of new American army forts, which marked the advancing frontier. At first, these forts were primarily manned by infantry, rendering them ineffective as the Comanche easily bypassed them. But soon, new light-cavalry regiments replaced the infantry, requiring a three-line fort system and a significant portion of the army’s pre-Civil War strength to maintain control over the Comanche territory in Texas.

The Comanches found posts like Fort Stockton at Comanche Springs particularly galling, as they were intended to block the “Great Comanche War Trail” leading to northern Mexico. According to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the United States was obligated to prevent raids into Mexico. However, between 1848 and 1853, Mexico filed 366 separate claims for Comanche and Apache raids that originated from north of the border, fueling further animosity.

The efforts to deal with the Texas Comanches extended beyond military force. In 1854, the Texas legislature allotted 23,000 acres for the United States to establish three reservations on the upper Brazos River for Texas tribes, including the Comanches. However, even after the establishment of these reservations, local settlers accused the reservation tribes, including the Penateka Comanche, of theft and other depredations, leading to escalating tensions.

In response to the discovery that bands of Kiowa and Comanche were using Indian Territory in Oklahoma as a sanctuary for raids into Texas, the Texas government urged the army to take greater action against the Comanches beyond the state’s borders. Between 1858 and 1860, the army’s new light-cavalry regiments launched an offensive against Comanches in Oklahoma. The Texas Rangers also took part, attacking a Comanche village and engaging in skirmishes.

Amid these conflicts, the peaceful Penateka Comanche were forced to leave Texas, along with other tribes like the Tonkawa, Caddo, and Delaware, who had previously served as scouts for the Texas Rangers. The situation became even more precarious with the outbreak of the Civil War, leading to the withdrawal of federal soldiers from the region. Confederate troops replaced them, and treaties were signed with Comanches in 1861, but the promised goods and services were never delivered due to the Confederacy’s financial constraints.

The Civil War presented a unique opportunity for the Comanches to seek revenge against the Tonkawa, whom they despised for their service with the Texas Rangers and their history of cannibalism. A massacre occurred, further escalating tensions in the region.

In the aftermath of the Civil War, peace efforts were made through treaties. The Little Arkansas Treaty of 1865 granted the Comanches and Kiowa a vast reservation in southwestern Oklahoma and the entire Texas Panhandle. However, disputes over annuities, broken promises, and the desperate state of affairs resulted in renewed hostilities.

The Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867 was another attempt to resolve the conflict through a peace conference in southern Kansas. The Comanches and Kiowa exchanged Comancheria for the new reservation in Oklahoma, but the treaty did not work as intended, leading to a starvation winter for many tribes. Some Comanches, like the Kwahada, did not sign the treaty and chose to remain on the Staked Plains, further complicating matters.

The Comanche raids continued, and in November 1868, Colonel Kit Carson led an expedition to chastise the Comanches and Kiowa. The First Battle of Adobe Walls almost ended in disaster for Carson, and despite later engagements, the situation remained tense.

The war persisted, and in October 1871, Texas civilians stole horses from the tribes at Fort Sill, while Comanches and Kiowa continued to raid Texas and Kansas. The army, led by Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie, launched a campaign to punish the Kwahada, resulting in hostages being taken and negotiations for their release. Texas Governor Edmund J. Davis later paroled Kiowa chiefs, hoping to quell the raids.

The situation remained volatile, with occasional war parties slipping off the reservation and raiding Texas. The continued hostility between the Comanches and settlers, as well as broken treaties and unfulfilled promises, would shape the region’s history for years to come.

Throughout the late 1860s and into the 1870s, the Comanche people found themselves embroiled in a complex web of conflicts, broken treaties, and shifting alliances. The encroachment of white settlers into Comancheria had triggered a series of clashes, leading to retaliatory raids, broken promises, and deep-seated animosities on both sides.

As the United States government attempted to enforce its treaties with the Comanches and other tribes, they faced numerous challenges. The annuities promised to the tribes in exchange for peace often fell short of expectations, causing widespread disappointment among the Comanche people. Instead of receiving the guns, ammunition, and quality goods they had hoped for, they were left with rotting civil war rations and subpar blankets that could hardly withstand the rain.

These unfulfilled promises, combined with the ever-encroaching white settlers, left the Comanches feeling frustrated and betrayed. As the frontier continued to expand westward, the Comanches’ traditional way of life came under increasing threat. The vast herds of bison, which had once provided them with sustenance and a marketable commodity through horse trading, were now rapidly dwindling due to overhunting by settlers and the expansion of railroads.

Moreover, the Comanche society had been significantly weakened by devastating epidemics of smallpox and cholera brought by the wave of immigration from the California Gold Rush in the late 1840s. These diseases had decimated their numbers and further eroded their ability to resist the encroachment of settlers.

The Texas Rangers played a crucial role in further exacerbating the tensions. Often operating beyond state lines, they pursued the Comanche into Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) and even into Mexico, retaliating for raids in Texas. While some Comanche divisions signed treaties and sought peaceful resolutions, others, like the Kwahada, remained defiant and refused to be bound by the agreements.

The situation became increasingly complex with the outbreak of the Civil War. The Comanche people found themselves caught in the crossfire of the conflict, with some factions aligning with the Confederacy while others maintained their hostility towards the white settlers and their interests. The chaotic nature of the war further complicated matters, leaving Comanches and other tribes uncertain about whom to trust and what actions to take.

The end of the Civil War brought a sense of hope for peace, as government commissioners met with the plains tribes to arrange a new treaty. The Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867 granted the Comanches and Kiowa a vast reservation in southwestern Oklahoma, intended to be a new home for these tribes. However, this move was met with resistance, as many Comanches chose to remain on the Staked Plains, refusing to accept the treaty’s terms.

As tensions continued to simmer, the Comanches and Kiowa found themselves in conflict with other Plains tribes like the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho, who had formed a general alliance against the encroaching settlers. This further complicated the situation, with various tribes vying for territorial control and limited resources.

The persistent violence and broken promises took a toll on both sides, leading to a vicious cycle of retaliatory raids and conflicts. The Comanche people, once known as fierce warriors, faced significant challenges as their traditional way of life and territory were threatened by an ever-expanding United States.

By the mid-1870s, the Comanches had mostly settled on a reservation in Oklahoma, but their population had dwindled, and they continued to face hardships and challenges. Their once-thriving society, reliant on the buffalo and their vast herds of horses, had been disrupted, leaving them grappling with the changes brought about by the relentless march of white settlers.

Despite their resistance and struggles, the Comanche people managed to preserve their cultural identity and some aspects of their traditional way of life. But the effects of colonization, broken treaties, and loss of land and resources had forever altered the trajectory of their society. As the United States government continued to exert control over their affairs, the Comanche people faced an uncertain future, trying to navigate the complexities of a rapidly changing world while holding on to the remnants of their proud heritage.

In the 19th century, the relentless pursuit of European settlers nearly drove the majestic bison to the brink of extinction. Once millions roamed freely across the continent, but by the late 1880s, less than a hundred remained in the wild. This drastic decline was not due to Indigenous hunting practices, where every part of the animal was used respectfully, but rather the mass slaughtering by settlers, who had their eyes set on the bison’s valuable skins and tongues alone. The rest of the animal, its once-mighty carcass, was left to rot and decay on the unforgiving ground.

The European hunters exploited the bison’s roaming behavior to their advantage. When one bison fell to a hunter’s gun, the others would instinctively gather around, unwittingly presenting themselves as targets. The ease with which one bison could be killed often meant the tragic destruction of an entire herd.

As settlers’ greed and destruction escalated, maps of the extermination of the bison showcased the devastating range reductions. Where once their domain stretched far and wide, now only scattered pockets of bison territory remained.

A poignant essay from the time painted a vivid picture of the relentless slaughter: “Thirty years ago millions of the great unwieldy animals existed on this continent. Innumerable droves roamed, comparatively undisturbed and unmolested… Many thousands have been ruthlessly and shamefully slain every season for past twenty years or more by white hunters and tourists merely for their robes, and in sheer wanton sport, and their huge carcasses left to fester and rot, and their bleached skeletons to strew the deserts and lonely plains.”

This senseless destruction of the bison also had profound consequences for the Indigenous peoples whose lives and cultures depended on the buffalo. While some tried to maintain their traditional ways, others were forced to adapt to new hunting styles to survive. Some even embraced the fur trade, altering their hunting methods to include horseback hunting, which allowed them to cover more ground and hunt more bison.

Yet, the commercial incentives for settlers were undeniable. Bison hunting became a means to economic gain, with trappers and traders profiting from the sale of buffalo fur. The harsh winters saw over 1.5 million buffalo put on trains and transported eastward. Bison leather found various uses, including making machinery belts and army boots, further binding Natives to the settlers’ economy.

The involvement of the US Army in the mass bison slaughter was one of the most tragic chapters in this dark tale. The federal government saw bison hunting as a tool to pressure Native tribes into reservations by depriving them of their primary food source. Without the bison, many Plains tribes were left with no option but to abandon their lands or face starvation.

General William Tecumseh Sherman advocated for the mass hunting of bison, believing it would force the Indigenous people to assimilate into “civilized” life. Other military leaders shared this sentiment, seeing the bison as a means to an end in taming the frontier.

President Ulysses S. Grant’s veto of an act that would protect buffalo from overhunting further exemplified the government’s lack of concern for the iconic animal. In their eyes, the bison’s demise would aid in the “forced assimilation” of Indigenous peoples.

The relentless decimation of the buffalo was, in many ways, emblematic of the larger struggle between settlers and Indigenous peoples. The buffalo’s fate became intertwined with the destiny of the Native tribes and served as a tragic symbol of the profound impact of colonization on the people and wildlife of the American plains.

In the frigid depths of winter, a spiritual leader of immense influence, Isatai’i, rose among the Quahadi Band of Comanches. With a claim of invulnerability to bullets, Isa-tai stirred the hearts of a colossal number of Indians, rallying them for massive raids. Meanwhile, a seismic shift occurred within the Kiowa’s political landscape, elevating the war faction led by the formidable Guipago, known as Lone Wolf “the Elder,” to a position of immense power.

In the Texas Panhandle, a tiny outpost named Adobe Walls stood vulnerable, surrounded by boundless wilderness. On a fateful day, June 27, 1874, Isa-tai’i and Comanche chief Quanah Parker unleashed a ferocious attack upon this outpost, leading an army of 250 warriors. The defenders, a mere 28 men and one brave woman, clung to the refuge of their few buildings, fortifying themselves against the onslaught. The echoes of the first Battle of Adobe Walls, decades earlier in 1864, reverberated through the air as the hunters and warriors clashed once more.

The hunters wielded their large-caliber buffalo guns with uncanny precision, firing from far greater distances than the Indians had anticipated. The fierce resistance of the defenders shattered the invaders’ hopes of victory, and their attack faltered. It was a moment of reckoning, as the hunters’ courageous stand defied all expectations, and their weapons proved mightier than the Indians had ever imagined.

In another encounter, the Kiowa warriors, led by the indomitable Lone Wolf, clashed with a patrol of Texas Rangers in the Lost Valley fight. The skirmish was relatively light in casualties, yet it intensified the already simmering tensions along the frontier, pushing the Army into an aggressive response.

The explosion of violence took the government by surprise, and the “peace policy” of the Grant administration was swiftly abandoned. General Philip Sheridan’s orders rang out like a thunderclap, commanding five army columns to converge upon the Texas Panhandle, hunting down the tribes relentlessly. The soldiers’ mission was to deny the Indians any safe haven and to attack them without mercy until they surrendered and submitted to the reservation system.

Across the Texas Panhandle, as many as 20 intense engagements unfolded between the Army and the indigenous tribes. The encounters were filled with tension, as the Indians sought to evade the relentless pursuit of the soldiers, while the Army scouts had access to boundless supplies and equipment. The war raged throughout the fall of 1874, and the unyielding pressure compelled an increasing number of Indians to surrender and seek refuge in the reservation system.

One notable battle took place at the Upper Washita River, where Captain Wyllys Lyman and his troops faced a formidable attack from a group of Comanches and Kiowas. The ensuing battle, known as Lyman’s Wagon Train, was a dramatic and intense clash, where courage and determination prevailed.

However, the most significant victory for the Army came at Palo Duro Canyon. Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie led his scouts to discover a sprawling village of Comanche, Kiowa, and Cheyenne, nestled amidst the rugged canyon terrain. The ensuing attack was swift and devastating, forcing the Indians to retreat, abandoning their horses and winter supplies. The battle left a profound impact, depleting the Indians’ vital resources and severely impacting their ability to sustain themselves.

As the months passed, the Red River War waged on, relentlessly wearing down the resistance of the once-powerful Southern Plains tribes. Finally, in June 1875, Quanah Parker and his Quahadi Comanches surrendered at Fort Sill, marking the end of the war and the last of the large roaming bands of southwestern Indians. The victory brought an end to the Texas-Indian Wars, leaving the Texas Panhandle open for settlement by farmers and ranchers, forever altering the region’s landscape and destiny.

The Texas Panhandle lay sprawled before the converging army columns like an untamed wilderness, a land teeming with ancient spirits and stories of a fierce indigenous people. General Philip Sheridan’s orders crackled through the air, commanding five mighty columns to muster their forces and converge upon the untamed expanse of the Texas Panhandle. Their target: the upper tributaries of the Red River, a domain believed to harbor the elusive tribes of the Southern Plains. The strategic design was simple yet ruthless – deny the Indians any safe haven, and unleash an unrelenting torrent of attacks until they were compelled to submit permanently to the reservation system.

Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie, a seasoned and resolute leader, commanded three of the formidable columns. Like a thundering storm, the Tenth Cavalry, under the steadfast Lieutenant Colonel John W. Davidson, surged westward from the strong fortress of Fort Sill. The Eleventh Infantry, led by the indomitable Lieutenant Colonel George P. Buell, advanced northwest from the mighty bastion of Fort Griffin. As for Mackenzie himself, a warrior with the heart of a lion, he spearheaded the Fourth Cavalry on a daring northern march from the stout walls of Fort Concho.

Yet, the forces that would converge upon this vast, untamed land did not end there. The fourth column, led by the cunning and experienced Colonel Nelson A. Miles, featured a powerful union of the Sixth Cavalry and the Fifth Infantry. With resolute determination, they advanced relentlessly southward from the unyielding stronghold of Fort Dodge. And in the distance, the fifth column emerged from the eastern horizon, the Eighth Cavalry commanded by the gallant Major William R. Price, marching with precision and purpose. This legion of 225 officers and men, along with six intrepid Indian scouts and two expert guides, had originated from the storied grounds of Fort Union, embarking on an arduous journey via Fort Bascom in New Mexico.

The convergence of these columns heralded the beginning of a relentless and continuous offensive against the tribes of the Texas Panhandle. As many as 20 fierce engagements ensued, each confrontation a momentous clash of cultures and survival instincts. The Army, a disciplined force of soldiers and scouts, relentlessly sought to engage the evasive and agile Indians at every opportunity. The tribes, on the other hand, journeyed with their women, children, and elders, striving to avoid direct confrontation with the overwhelming force that bore down upon them.

Yet, when destiny’s hand drew them together, the resolute warriors of the Southern Plains attempted to escape before the Army could force them into submission. However, the cost of a successful escape was steep, leaving behind precious horses, sustenance, and vital equipment. The Army and its Indian scouts, unfettered by such constraints, had access to a wealth of supplies and equipment, and they frequently wielded the might of fire, burning anything that the retreating Indians left behind. Their relentless campaign seemed inexhaustible, capable of continuing indefinitely, like the boundless horizon of the Texas Panhandle.

Throughout the fall of 1874, the war’s crescendo echoed across the vast expanse, and with every passing day, increasing numbers of Indian tribes were compelled to relinquish their nomadic existence and seek refuge at Fort Sill, succumbing to the reality of the reservation system.

Among the countless battles that colored the landscape of the Texas Panhandle, two stand out as enduring legends etched into history. The Battle of the Upper Washita River, a saga of bravery and tenacity, unfolded on September 9, 1874. As Captain Wyllys Lyman and his wagon train of rations approached Camp Supply, they were confronted by a formidable force of Comanches and Kiowas. Like a fortress amid the prairie, the wagon corral became a bastion of courage, with Lyman and his 95 troops fending off an adversary that numbered around 400. In a valiant effort to seek aid, a scout raced to send word to Camp Supply. Soon after, the valiant Sixth Cavalry, without rest and amidst a relentless rainstorm, rode to their rescue. When the dust settled, it became known as both the Battle of the Upper Washita River and the Battle of Lyman’s Wagon Train – an epic tale of endurance and camaraderie amid the vast, untamed frontier.

In the heart of September, another fateful clash unfolded near the rugged terrain of the Palo Duro Canyon. With steely resolve, Tonkawa and Black Seminole Scouts advanced ahead of the Fourth Cavalry, their eyes and senses ever alert to the lurking danger. They narrowly escaped an ambush by the cunning Comanches near the Staked Plains, alerting Col. Mackenzie of their foe’s whereabouts. Their intelligence led to the largest Army victory of the war, as Mackenzie’s scouts discovered a sprawling village of Comanche, Kiowa, and Cheyenne, nestled within the canyon’s embrace. At dawn on September 28, Mackenzie’s troops launched a ferocious attack, descending upon the unsuspecting village like a thunderbolt. The startled Native Americans, caught off-guard and without time to gather their horses and provisions, faced an overwhelming onslaught. Their warriors fought with desperate valor to shield their women, children, and pack animals. But, the persistent fire of the troops forced them to retreat, and the warriors began falling back. The impact was immense and devastating; Mackenzie’s men razed over 450 lodges and obliterated countless pounds of buffalo meat, a vital source of sustenance for the tribes. In addition, they captured 1,400 horses, most of which were ruthlessly shot to prevent the Indians from recapturing them.

The Battle of Palo Duro Canyon became a defining moment, leaving a profound mark on the war’s trajectory. While most encounters resulted in little to no casualties, the cumulative loss of resources, sustenance, and mounts weighed heavily upon the tribes. An Indian band caught on foot and with limited options for food found themselves at the mercy of their adversary, with little choice but to surrender and seek refuge in the reservation system.

Finally, in June 1875, the relentless pursuit of the Army culminated in a decisive outcome, marking the official end of the Red River War. Quanah Parker and his band of Quahadi Comanches, the last of the large roaming bands of southwestern Indians, entered Fort Sill and surrendered. Their submission, coupled with the extermination of the buffalo, left the Texas Panhandle permanently open to the onward march of settlers – farmers and ranchers who would irrevocably shape the destiny of the untamed land. With this final military defeat, the once powerful Southern Plains tribes were forever changed, and the curtain fell upon the Texas-Indian Wars, leaving behind a legacy that resonated through the ages.

In the waning years of the 19th century, the once mighty Kwahadi Comanche found themselves at a crossroads of history. Their traditional way of life had been uprooted by the relentless advance of the American army, and their once abundant food source, the buffalo, had been decimated to near extinction. The resilient Comanche, led by the indomitable Quanah Parker, finally succumbed to the mounting pressure, and in 1875, they made the fateful decision to surrender. Alongside Colonel Mackenzie and Indian Agent James M. Hayworth, Quanah Parker guided his people to their new home on the Kiowa-Comanche-Apache Reservation in the southwestern Indian Territory.

The Star House, nestled within the vast expanse of Cache, Oklahoma, became Quanah Parker’s sanctuary and symbolized his authority as a respected chief. The spacious, two-story dwelling stood as a testament to his growing influence and prosperity. Inside its walls, there was a bedroom for each of his seven wives and their children, a testament to the customs of his ancestors. Quanah Parker himself had a rather plain private quarters, but beside his bed, framed photographs of his mother Cynthia Ann Parker and younger sister Topʉsana served as cherished mementos, connecting him to his past and driving his vision for the future.

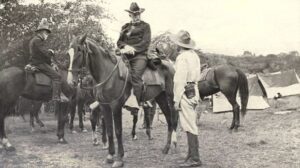

A remarkable chapter in Quanah Parker’s life unfolded when he embarked on hunting trips with none other than President Theodore Roosevelt himself, who held him in high regard. The President, captivated by Quanah Parker’s warrior spirit and wisdom, often sought his company and valued his counsel. Despite these close ties to the world of the white man, Quanah Parker clung to his native roots, rejecting both monogamy and traditional Protestant Christianity in favor of the Native American Church Movement, which he co-founded. This new spiritual path became a sanctuary for him, an avenue to embrace his ancestral heritage while navigating the shifting tides of the modern world.

However, Quanah Parker’s most profound and enduring friendship blossomed with the Burnett family. Their bond transcended the boundaries of culture and race, forging an unbreakable connection that was a testament to the respect and admiration they held for each other. The Burnett family, known for their cattle empire, welcomed Quanah Parker into their fold, treating him as an honored guest and a true friend. A unique exhibition of cultural artifacts gifted from the Parker family to the Burnetts attested to the depth of this relationship.

Together, Quanah Parker and the Burnetts experienced a myriad of adventures. From parades with a large group of Comanche warriors at the Fort Worth Fat Stock Show to wolf hunting expeditions with President Roosevelt, they shared moments that solidified their mutual admiration and respect. Burnett’s advocacy for Native American rights and his respect for their customs endeared him to the tribes. The Comanches, recognizing his importance in their lives, bestowed upon him the name “Mas-sa-suta,” signifying “Big Boss” in their language.

Quanah Parker’s legacy extended beyond his interactions with the Burnett family and President Roosevelt. He emerged as a trailblazer, becoming one of the key leaders of the Native American Church movement. The sacred peyote medicine, a central element of the movement, was a sacrament bestowed upon the Indian people, and Quanah Parker was instrumental in its adoption and integration into their spiritual practices.

The passage of time eventually led to Quanah Parker’s passing in 1911, and he was laid to rest at the Post Oak Mission Cemetery near Cache, Oklahoma. His final resting place bore the epitaph that celebrated his extraordinary journey – a lifetime that traversed from a Stone Age warrior to a statesman of the Industrial Revolution, from a fierce leader who never lost a battle to a visionary who embraced change while preserving his heritage.

As the sun sets on the legacy of Quanah Parker, it is impossible to ignore the impact he left on history. His life symbolized the resilience and adaptability of the Native American tribes, their ability to bridge cultures, and their relentless pursuit of a dignified existence in a rapidly changing world. The spirit of Quanah Parker, like the sacred peyote medicine he championed, remains alive and woven into the fabric of Native American history and cultural identity. His name will forever echo through the annals of time as a testament to the unyielding spirit of his people and the lasting legacy of an extraordinary leader.

Nestled in the heartland of Oklahoma, the Comanche Nation stands strong under the guiding principles of its Constitution. At its helm is the esteemed Tribal Council, an assembly of wisdom and authority comprised of all enrolled members aged 18 and above. Within the Council, seven elected officials rise to prominence, each carrying the weight of their people’s hopes and dreams. The Chairman, Vice-Chairman, Secretary/Treasurer, and the four esteemed Committeemen, united under the banner of the Comanche Business Committee (CBC), form the nucleus of governance.

Every stride the Comanche Nation takes is fueled by the Chief of Staff, the torchbearer responsible for the day-to-day operations of the Tribal Government. Their shoulders bear the burden of ensuring the tribe’s aspirations align with its mission as defined by the Constitution of the Comanche Nation.

Emblazoned in the core of this mission is the unwavering dedication to define, establish, and safeguard the rights, powers, and privileges of the tribe and its cherished members. A profound commitment emerges to uplift the economic, moral, educational, and health status of the Comanche people, for they are bound by a sacred duty to seek the well-being of their kin. Their hand outstretches to the United States, forging alliances to create mutual programs, for their destinies are interwoven in shared pursuits.

Yet, it is not just in the political realm where their energies converge. The Comanche Business Committee weaves a tapestry of prosperity and preservation, striving to improve the economic status while stewarding the Nation’s natural resources and safeguarding its cultural heritage. Their vision takes root in the rolling landscapes of their main headquarters, where just 9 miles north of Lawton, Oklahoma, the heartbeat of the Comanche Nation echoes through the land.

In the shadows of these sacred hills, approximately 17,000 enrolled tribal members breathe life into the Comanche Nation. Among them, around 7,000 souls find solace within the tribal jurisdictional area, a realm that encompasses the bustling domains of Lawton, Ft. Sill, and the surrounding counties. Here, the legacy of the Comanche thrives, passing down from generation to generation, a living testament to the strength, unity, and resilience of a people that have endured the tests of time.

In these hallowed lands, the Comanche Nation unfurls its vibrant tapestry, a tale of tenacity and triumph. Each thread woven by their governance, their aspirations, and their unwavering spirit, etches a legacy that will endure the ebb and flow of history’s tides. Through storms and stillness, the Comanche Nation stands resolute, a beacon of hope and progress, forever guided by the spirit of their ancestors and the dreams of their future.

Amidst the boundless expanse of the Great Plains, a fierce and indomitable tribe arose, casting an unyielding shadow over the land. They were the Comanche, masters of their realm, rulers of the Comancheria, and their presence struck fear into the hearts of those who dared to cross their path. With an iron fist, they commanded respect and awe, leaving a legacy etched in the annals of history.

From the very heart of their culture, they recognized the sacred bond between man and horse, unlocking the secrets of horsemanship long before others could even fathom its significance. Mounted on the backs of these majestic creatures, they became an unstoppable force, their swift and skilled maneuvers on horseback akin to poetry in motion.

Their name echoed through the canyons and prairies, reverberating in tales of daring exploits and fearsome battles. So powerful was their impact that it beckoned the formation of the Texas Rangers, a valiant force brought to life to counter the ever-present might of the Comanche.

But it wasn’t just their prowess on horseback that left an indelible mark on the pages of history. The Comanche were trailblazers, catalysts of innovation. They inspired the very creation of the six-shooter revolving pistol, a weapon of formidable design that would change the course of warfare forever. With every deadly spin of its chamber, it symbolized the sheer force of the Comanche spirit.

This is not a mere chapter in history; this is an epic tale, the saga of a people who sculpted their destiny with bravery, cunning, and unwavering resolve. The Comanche stood as titans on the Great Plains, shaping the very landscape upon which they tread.

Through the haze of time, their legend lives on, an awe-inspiring tapestry woven with the threads of courage and tenacity. Their Comancheria pulsed with life, vibrant and fierce, a testament to the strength and unity of a tribe unlike any other.

The echoes of their triumphs still whisper in the winds, and their legacy endures in the hearts of those who remember. The Lords of the Great Plains, the Comanche, forever etched in the annals of time, their story will forever captivate and inspire, a relentless testament to the unyielding spirit of a people who defied the odds and left an indomitable mark upon history’s canvas.